Last updated on December 13, 2020

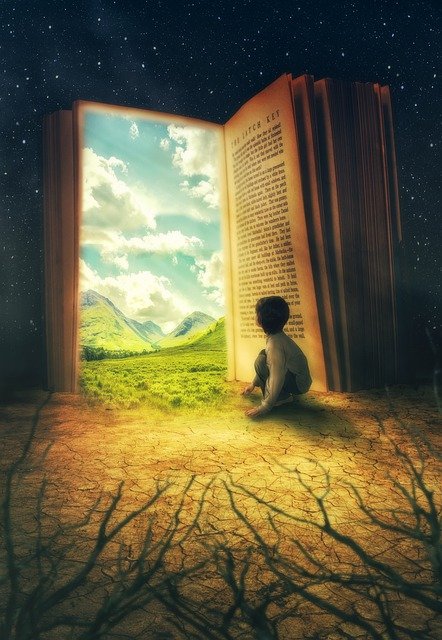

Last week’s blog on imagination concluded by observing that we seem to instinctually sense that there must be answers to the questions: “Who am I and what on earth am I here for?” Even as many people avoid or reject the possibility of answers at all. But this very natural need for an “answer” of some kind tends to manifest itself in a search for stories. So what stories do we pick?

Naturally, we tend toward those narratives that are most compatible with our experience and those stories that are most desirable. We gravitate toward what we want to be true, to what makes us feel good about our future and ourselves. We also tend toward those stories and those storytellers who seem to have discovered the assurance that we do not have. “Well, they seem to have figured this out. Maybe I’ll listen in.” We may also come to believe that there is only one story we could accept, perhaps because of the color of our skin, our national origin, sexuality, or family.

And this is where the imagination finally comes in. Well, it’s been involved the whole time, but it may be clearest here.

Our imagination is where we hold and create the story or stories – ultimately incomplete – that make sense of our experience. It’s our intuition of how all of life fits together as a whole. The story becomes a pre-rational reference point for the way we define concepts, the way we determine what we love, hate, desire, and fear. It is how we conceive of what is possible and impossible, what is beautiful and ugly, and what is right and wrong.

Because the imagination forms our concepts, it also shapes the way we reason. By “concept” I mean the way in which the imagination connects the universal and the particular – the eternal and the temporary. We associate particular words and descriptions to particular experiences to make sense of them. Reason is the more deliberate, systematic way we think through our actions and reactions, through our “answers” and applications. But reason depends on the concepts formed by our imagination.

Imagination (along with our concepts and reason) shapes and is shaped by what we love and hate; that is, it shapes our will and behavior. Claes Ryn defines will as “the generic, categorical name for that infinity and variety of impulse that orients the individual to particular tasks.” (Ryn, 1997 p. 147) Humans think and do what they will and desire to do. The will “sustains” and directs human character and behavior, but the direction that our will takes is informed by the imagination. The will/desire becomes aware of itself by means of the imagination. (Ryn, 1997 p. 148) We might think of the will, then, as a steering wheel, reason as the GPS, and the driver as the imagination (not a perfect metaphor…I know). We imagine what we will/desire and we will/desire what we imagine.

Put the will, imagination, and reason together and we begin to see a picture of how and why human beings do what they do. We have a will and we imagine the reality that we will act in as, and before, we act into it.

Reality is not subjective, though. There is a reality which exists independent of our imagination. But how attuned that imagination is to actual reality has enormous importance for our everyday lives.

If truth, goodness, and beauty in any objective, universal sense, do not exist, then asking about the quality of one’s imagination – as I intend to do – is pointless. No comparison can be made qualitatively. But if there is a moral and physical reality in which one’s imagination can be grounded, then wouldn’t we want to be as attuned to that reality as possible? Perhaps this is why, despite the nihilism that characterizes our generation, we still gravitate toward something that at least seems like a compelling account of reality. It’s as if we, as human beings, were not meant to be nihilists after all (as C.S. Lewis so eloquently showed). At the same time, even if we accept reality as real and knowable, we may nevertheless run from it. We may find reality too hard to handle. So we try and escape. We run from reality. Perhaps this was the reason for the move toward nihilism in the first place. Recognition of objective moral values and responsibilities ends up imposing on us and we may have to make sacrifices or repress darker desires. Would it not be easier to just say, “It’s all relative and whatever I say is right and true is right and true because I said so!”

This is the point where I turn to one of the most striking examples of the power of imagination: the story of the Nazis’ rise, rule, and fall. I specifically point to a brilliant, but little known documentary on the aesthetics of the Nazis. It’s called The Architecture of Doom, directed by Peter Cohen and released in 1989. I encourage you to take a look, as it is available online for free (though I’m not sure its availability is legal)

If we gravitate toward stories to help make sense of our lives, and we want those stories to correspond to reality, why do we so easily fall for stories that lead to death, violence, and destruction? How do we resist them? We’ll pick up with this question next time.

Comments are closed.